Uma Sutam Ganesha: His Mother’s Son

Texts and tradition hail Ganesha as Uma-sutam, the son of Uma or Parvati, otherwise a formal epithet like many other but perhaps with a greater dimensional breadth than any, even than his name ‘Ganesha’. No epithet, even any contextual to his father Shiva, defines him so completely as does ‘Uma-sutam’.

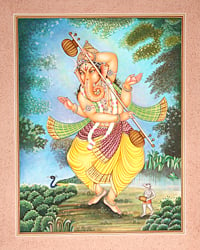

Not only a visual image or overall personality or character, if the terms might be used for a divinity like Ganesha, he has hardly anything common with any god of the pantheon, even Shiva, his father, except his dance-cult, though while in the case of Shiva dance is an act of body and mind that he performs at times, in the case of Ganesha dance is his being, his body and the essence of his mind he lives with.

Ganesha does not perform dance, it reveals into his form – something inherent and basic. The distinction that makes Ganesha different from other gods is his distinction as the son of Parvati : the ‘Uma-sutam’.

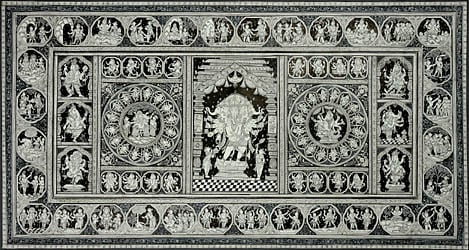

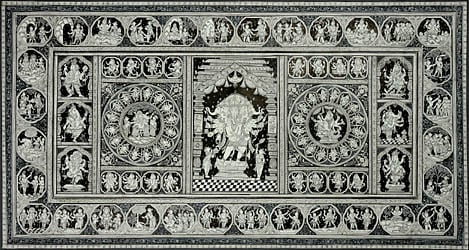

A trans-sectarian divinity worshipped by different names in different religious orders in India, Lord Ganesha has in Hindu pantheon a status on par with, or rather above, the great Trinity : Shiva, Vishnu and Brahma, for it was by his help that each of them accomplished his objective, not Ganesha by their help. A trans-sectarian divinity worshipped by different names in different religious orders in India, Lord Ganesha has in Hindu pantheon a status on par with, or rather above, the great Trinity : Shiva, Vishnu and Brahma, for it was by his help that each of them accomplished his objective, not Ganesha by their help.

Shiva revives him to life by transplanting the elephant head on his torso and nominates him the commander of ‘ganas’, but it all amounts to mere correction of the error that Shiva had himself committed and to pacify an enraged mother threatening to destroy the universe unless her son was revived, and Shiva knew she could do it. Thus, despite that Shiva gives him a new life, Ganesha remains a mother’s son. Whatever the metaphysical position, the tradition perceives duality between the manifest cosmos on the one hand and either of the Trinity on the other; Ganesha himself is the manifest cosmos, duality diluting into his very form – an entirety, a presence beyond act.

Illuminating the entire cosmos and every mind with good and auspiciousness, or a house with abundance and riches – his primary objectives as a divinity and as assigned in texts, Lord Ganesha accomplishes by his mere presence, not by an act of body or mind. Different from other gods who are essentially operative, even Vishnu, a name that literally means ‘one who expands and pervades’ – broadly a ‘presence’, but discovering himself primarily in an act, Ganesha is non-operative, an entity that accomplishes every errand by mere presence.

Unlike other gods or the Divine Female – Devi, who emerged for accomplishing one objective or other, Ganesha had his origin in a desire for constant presence, at the most for keeping the doors – another form of presence. Even his confrontation with Lord Shiva as door-keeper is incidental to his presence. Nowhere in the entire body of mythology his presence is incidental to an act. As suggests the universal Ganesha-mantra : ‘Shri Ganeshaya namah’, harbinger of riches and abundance, Ganesha only assures that ‘Shri’ or Lakshmi, the goddess of riches, shall precede him when his presence is invoked; he does not drag riches to a coffer.

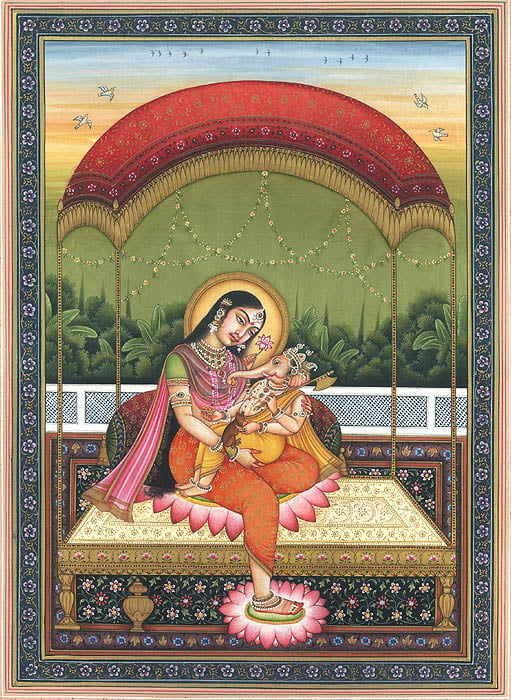

Obviously, while others are the gods by act, Ganesha is the god, and the only in the pantheon, by presence, and this aspect : accomplished all errands by mere presence, is the mother-given. Ganesha is said to rise out of the waste of the herbal paste rubbed by Parvati off her body. As the scriptural tradition has it, Lord Shiva was often away and a lonely Parvati was as often occupied by thoughts of a son who could by his company relieve her of her loneliness.

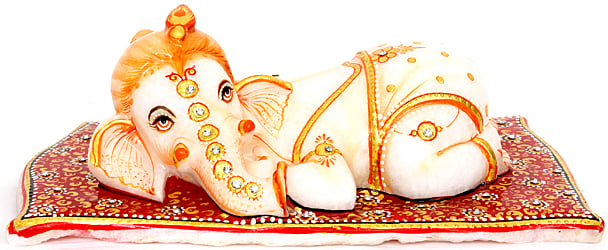

One day, when bathing and absorbed in similar thoughts, Parvati inadvertently moulded the herbal paste she removed from her body into a tiny anthropomorphic figure. The idol in hand Parvati wished it had life, and the other moment the idol transformed into a living child. Not born of Parvati but produced by sharing her, and her alone, every inch – the body and the mind, and all playfully, and by sharing the nature : the herbs the paste of which composed his figure, besides the subsequently added elephant trunk, this strange origin shapes Ganesha’s basic character – essentially a mother’s son.

Though at a subsequent stage, whatever the myths or circumstances necessitating it, Lord Shiva undoes this birth of the child and assimilating into its form another aspect of cosmos : an elephant trunk, gives him life anew, his ultimate form, as also the name Ganesha, and the fatherhood to the twice-born, the innocent plumpish looking Ganesha ever remains, essentially and exclusively, the mother-born, the product of an innocent playful mind filled with positive energy desiring creation and effecting it.

Parvati had other option for relieving her of her loneliness. She could insist on Shiva to stay back but it would amount to obstructing him from performing, which – the obstruction, was not the part of Mother Parvati’s being. Legends acclaim that after he transplanted the elephant head on Ganesha’s torso, Lord Shiva put his ‘ganas’, the all-obstructing unruly elements of cosmos, under the command of the newborn and named him Ganesha; however, it was from Parvati, who instinctively disapproved even innocent obstructions, to affect an act that Ganesha inherited his nature to not allow detrimental forces : ‘vighnas’, to operate.

Curving ‘vighnas’ was inherent to Ganesha, something inborn, the character of the blood, Shiva’s delegation of powers to command them was only magnification of this inborn aptitude.

Either by curving ‘vighnas’, removing or commanding them, Ganesha ensures smooth detriment-free beginning and accomplishment. Essentially the god of auspiciousness Ganesha is the only divinity in Hindu pantheon, or rather in the entire sectarian hierarchy of India, who at no point of time ever blessed, or even punished or destroyed, a wrong, which his father Lord Shiva, or Vishnu, Brahma and other gods often did. ‘Wrong’, it seems, was not a word in the dictionary of Ganesha.

The entire mythology abounds in legends when one wrong-doer or other is seen impressing by his ill-intended penance one of the Trinity, or any of the cosmic gods like Sun or Varuna, and winning from them a boon endangering sometimes even the cosmic order. Strangely no such evil forces are ever seen approaching Ganesha, perhaps the awe-inspiring lustre of an otherwise simple, cool, quiet and light-hearted Ganesha, a mighty laser-ring that his divine aura created around him, thwarted their ill designs before they dared come close to him.

This aspect of Uma-sutam : his inherent power to ward off evil and to ensure detriment-free beginning was seen by texts also during very early phase of Ganesha-related theology. Yajur-Veda, the earliest of texts alluding to Ganesha , lauds him as ‘Gananama twa Ganapati’, the lord of ‘ganas’ – known and unknown cosmic forces influencing human life, order and environs, not always adversely but often uncontrollably. Other early texts equate ‘ganas’ with ‘vighnas’, the forces that obstruct.

Thus, Ganesha, Vinayaka or Vighnesha – ‘vighna nighna karam’, one who eliminates obstacles, was seen as commanding both. Hence for ensuring obstruction-free beginning and accomplishment ‘Ado pujya Vinayaka’ – worship Vinayaka first was what Lord Vishnu himself ordained and reflects in the Vedas, Shrutis, Smritis, Upanishadas, Puranas … The Brahmavaivarta Purana alludes to Lord Vishnu as proclaiming : ‘Sarvagre tawa puja … sarva pujyashcha yogindra bhava’ – you are the first I worshipped, O conqueror of passions, you would be worshipped by all (13/2) for ‘Yasya smaran matren sarvavighno vinasyati’ – just by commemorating him the forces that impede are eliminated, and objectives, achieved. This power of Uma’s son was put to test many a time. Brahma was ordained to create a world of numbers, measurable, subject to rule and that which decayed and had an end; however, the unruly ‘ganas’ – cosmic elements, ‘pramatha’ – the innumerable, ‘bhuta’ – the unfathomable, ‘yaksha’ – the unending, and ‘rakshasa’ – the imperishable, disabled him from doing so. Thereupon Brahma commemorated Ganesha who commanded ‘ganas’, ‘pramatha’, ‘bhuta’, ‘yaksha’ and ‘rakshasa’ and helped Brahma create a world as he was ordained to create : the mortals’ world.

Vishnu had not only ordained Vinayaka’s ‘ado puja’ but himself invoked Ganesha before he vanquished Bali. Alike, Shiva is said to have invoked Ganesha before he destroyed Tripura, Durga, before she killed Mahishasura, great serpent Shesha, before it lifted the earth on its hood, Kamadeva, before he shot his arrows of love for conquering the universe, and sage Vyasa, before he composed the great epic Mahabharata. The belief that Ganesha accomplished everything undertaken obstruction-free was so firmly set into the tradition that even a number of medieval texts in Persian begin with invocation offered to Ganesha.  Full of zeal, energy, sportiveness, mischievousness in eyes, carefree disposition, cool, soft, simple, benign, child-like innocent looking Ganesha is essentially the mother’s son – Uma-sutam. Despite a massive build with a large elephant trunk Ganesha is strangely feminine. He enjoys dancing,blows a flute, Full of zeal, energy, sportiveness, mischievousness in eyes, carefree disposition, cool, soft, simple, benign, child-like innocent looking Ganesha is essentially the mother’s son – Uma-sutam. Despite a massive build with a large elephant trunk Ganesha is strangely feminine. He enjoys dancing,blows a flute,

and plays on any kind of musical instruments he happens to have in hand. Ganesha does not approve any kind of violence, cruelty, vengeance, punishment, even harshness or an inclination to harm. He carries instruments of war, at least a battle-axe or goad in one of his four, six, eight or ten hands, but is not known to have ever used them.

Sportive Ganesh inflicts on wrong-doers even penalties as part of a game, compassionately and not without sharing the feeling of pain, or any, involved in it.  Ganesh had a child-like weakness for laddus along other eatables, mangoes, pomegranates, sugarcane, bananas etc in particular: the foremost attributes of his imagery. one day at a feast offered by gods Ganesha ate more ‘laddus’ than his abdomen could contain. For relieving of heaviness he set out towards the forest for a walk. When in mid-forest, serpent Vasuki passed across. Horrified by the sight of the serpent his mouse he was riding on threw him away and fled for life. A heavy jerk, it bursts Lord Ganesha’s abdomen with ‘laddus’ rolling out. Ganesh had a child-like weakness for laddus along other eatables, mangoes, pomegranates, sugarcane, bananas etc in particular: the foremost attributes of his imagery. one day at a feast offered by gods Ganesha ate more ‘laddus’ than his abdomen could contain. For relieving of heaviness he set out towards the forest for a walk. When in mid-forest, serpent Vasuki passed across. Horrified by the sight of the serpent his mouse he was riding on threw him away and fled for life. A heavy jerk, it bursts Lord Ganesha’s abdomen with ‘laddus’ rolling out.

The moon enjoying the cool translucent night with its wives saw the incident and could not help smiling and make fun of it. The moon’s arrogance annoyed him but not an arm he removed one of his tusks and hurled it on the impertinent moon. The moon had a scar to keep him reminding against such mischief in future and at the same time the compassionate Ganesha took the punishment’s equal pain on him. Serpent Vasuki’s fault was in its movement by which it frightened a tiny mouse. Ganesha picked it and tied it like his waist-band around his belly curtailing the serpent’s all movements as in a jail-term.

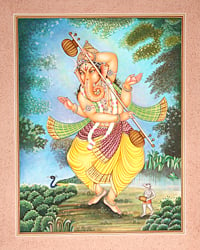

Dance revealing in every aspect of Ganesha’s being is the subtlest expression of his softness. Maybe, the artists : painters, sculptors, wood-carvers … were fascinated by queer contrast that they discovered in delicate moves of dance and the elephant god’s voluminous figure, but far from a creation of a fanciful mind or a mere aesthetic manipulation it is in dance that Ganesha has the source of his energies : dance not only energizes his body or ignites his kinetic and divine energies but by its myriads of multiplications transforming into a radiance of multi-million suns each move of his dance creates around a power-circuit that purifies the space of prevailing evil and prevents any from entering. Apart a curious anatomy that the curved trunk waving around, huge body surging with rhythm and mincing feet afford to eyes, dance is inherent and fundamental in Ganesha’s cult.  Not battlefield, or clamour of arms, blood-shed or killing, like his father Shiva who discovered his ultimate weapon in dance by which he dissolves the cosmos at the end of its tenure, not a drop of blood being shed, Ganesha ignited his divine energies in dance – his first preference, the lustre of which rent the multi-million layers of darkness, destroyed evil and illuminated the world and all minds. Not battlefield, or clamour of arms, blood-shed or killing, like his father Shiva who discovered his ultimate weapon in dance by which he dissolves the cosmos at the end of its tenure, not a drop of blood being shed, Ganesha ignited his divine energies in dance – his first preference, the lustre of which rent the multi-million layers of darkness, destroyed evil and illuminated the world and all minds.

He has strange power to inspire artists’ imagination to discover his ever new forms, now in thousands. In inspiring this creative imagination dance has been the most potent instrument providing the widest possible scope for rhythmically gesticulating the elephant god’s otherwise voluminous body and create dramatic effects. Far more and far different from a mere body-posture or an act of body or mind, dance is his subtlest instrument by which Lord Ganesha accomplishes his supreme cosmic role : warding off evil, promoting good and auspicious and illuminating the universe with divine light.

A mild smile, mischievously blinking eyes and a carefree relaxed mood define people’s image of the harmless little god. A child’s toy-chamber, roadside mud-platform or tiny shrine, or a huge monumental temple, Ganesha is everywhere a lovable deity.

An auspicious presence ensuring obstruction-free beginning and happy accomplishment Ganesha does not sanctify ends, except when an end precedes a beginning. Death rites do not begin by invoking Ganesha. His name or graphic symbol would not appear on papers seeking dissolution of marriage, partnership or firm, or declaring bankruptcy, lunacy or disentitlement.

In preceding century, during India’s freedom movement, Ganesha was the subtlest instrument of social reform and political awakening. The nation has on Ganesha-chaturthi – the fourth day of the white half of Bhadra, the sixth month under Indian calendar, on which Ganesha is believed to emerge, a weeklong country-wide annual celebration dedicated to Ganesha. In preceding century, during India’s freedom movement, Ganesha was the subtlest instrument of social reform and political awakening. The nation has on Ganesha-chaturthi – the fourth day of the white half of Bhadra, the sixth month under Indian calendar, on which Ganesha is believed to emerge, a weeklong country-wide annual celebration dedicated to Ganesha.

The hymns-chanting crowds of devotees believe that ‘Bappa’, as the loving ones call him, would come and his presence would promote love, right wisdom, good sense and mutual trust, bring prosperity and weal and make minds liberal, considerate, sensitive and responsible. Whatever his name, form or origin, people love him, and more so because good and right-doing are his principal attributes.

This article by Prof. P.C. Jain and Dr. Daljeet. Prof. Jain specializes on the aesthetics of literature and is the author of numerous books on Indian art and culture. Dr. Daljeet is the curator of the Miniature Painting Gallery, National Museum, New Delhi. They have both collaborated together on a number of books.

References & Further Reading: - Mudgala Purana

- Brahma Vaivarta Purana

- Matsya Purana

- Ganesha-Anka, Kalyana, Gita Press, Gorakhpur

- Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami: Loving Ganesa

- Oxford:: Ganeshaa - A Monograph of the Elephant Faced God

- Dr. Daljeet: Lord Ganesha; Shri Ganapate Nama

|