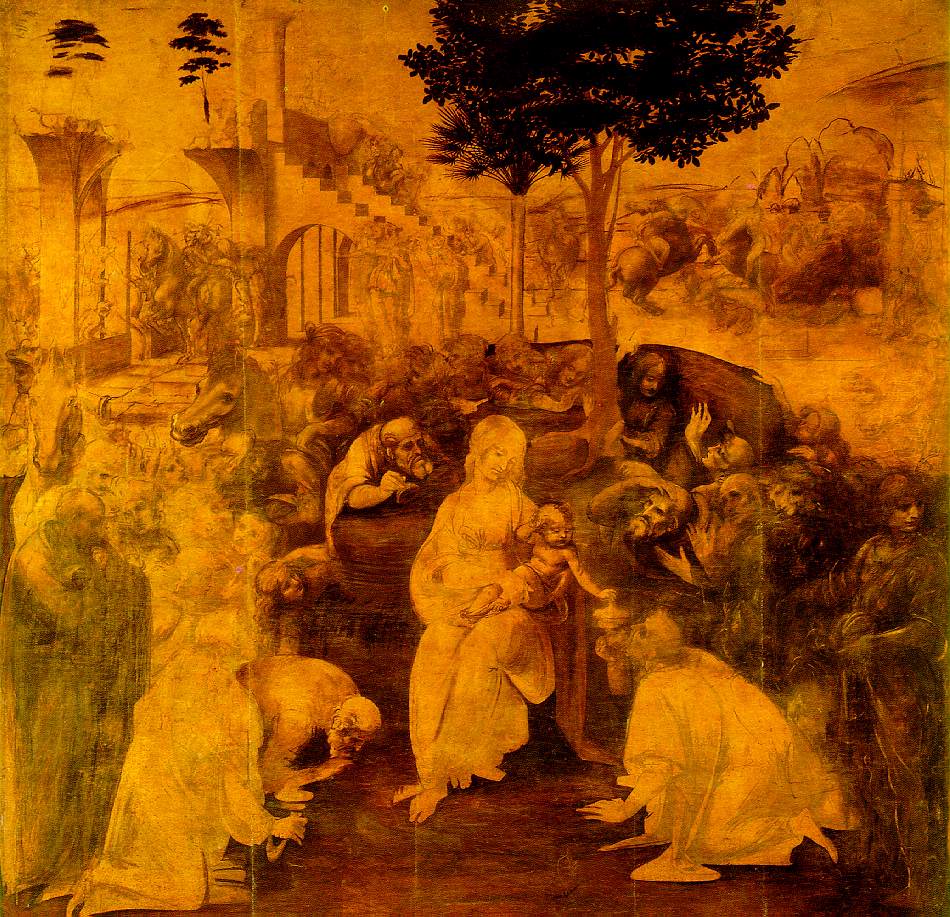

Adoration of the Magi (Filippino Lippi)The Adoration of the Magi is a painting by the Italian Renaissance painter Filippino Lippi. It is signed and dated at 1496. It is housed in the Uffizi of Florence. The panel was painted for the Convent of the San Donato agli Scopeti, in substitution of the one commissioned in 1481 to Leonardo da Vinci, who left it unfinished. In 1529 it was acquired by Cardinal Carlo de' Medici and in 1666 it became part of the Uffizi collection. Filippino Lippi followed Leonardo's setting, in particular in the central part of the work. Much of its inspiration was clearly derived from Botticelli's Adoration of the Magi, also in the Uffizi: this is evident in the disposition of the characters on the two sides, with the Holy Family portrayed in the centre under. Similarly to Botticelli's work, Filippino also portrayed numerous members of the Medici cadet line, who had adhered to the Savonarolian Republic in the period in which the work was executed. on the left, kneeling and holding with a quadrant, is Pierfrancesco de' Medici. Behind him, standing, are his two sons Giovanni, holding a goblet, and Lorenzo, from whom a page is removing a crown. The general style is that of Filippino's late career, characterized by a greater care to details and by a nervous rhythm in the forms, influenced by the knowledge of foreign painting schools (as also in the landscape of the background). Reference: Page at artonline.it (Italian)Adoration of the Magi (Gentile da Fabriano) The Adoration of the Magi is a painting by the Italian artist Gentile da Fabriano. The work, housed in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy, is considered his finest work, and has been described as "the culminating work of International Gothic painting", [1] The painting was commissioned by the Florentine literate and patron of the arts Palla Strozzi, at the arrival of the artist in the city in 1420. Finished three years later, it was placed in the new chapel of the church of Santa Trinita which Lorenzo Ghiberti was executing in these years. The works shows both the international and Sienese schools' influences on Gentile's art, mingled with the Renaissance novelties he knew in Florence. The panel portrays the path of the three Magi, in several scenes which start from the upper left corner (the voyage and the entrance into Bethlehem) and continue clockwise, to the larger meeting with the Virgin and the newborn Jesus which occupies the lowest part of the picture. All the figures wear splendid Renaissance costumes, brocades richly decorated with real gold and precious stones inserted in the panel. Gentile's typical attention for detail is also evident in the exotic animals, such as a leopard, a dromedary, some apes and a lion, as well as the magnificent horses and a hound. The frame is also a work of art, characterized by three cusps with tondoes portraying Christ Blessing (centre) and the Annunciation (with the Archangel Gabriel on the left and theMadonna on the right). The predella has three rectangular paintings with scenes of Jesus' childhood: the Nativity, the Flight into Egypt and the Presentation at the Temple (the latter a copy, the original being in the Louvre in Paris). Reference: 1.^ Timothy Hyman; Sienese Painting, p. 140, Thames & Hudson, 2003 ISBN 0500203725.Adoration of the Magi (Leonardo) The Adoration of the Magi is an early painting by Leonardo da Vinci. Leonardo was given the commission by the Augustinian monks of San Donato a Scopeto in Florence, but departed for Milan the following year, leaving the painting unfinished. It has been in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence since 1670. The Virgin Mary and Child are depicted in the foreground and form a triangular shape with the Magi kneeling in adoration. Behind them is a semicircle of accompanying figures, including what may be a self-portrait of the young Leonardo (on the far right). In the background on the left is the ruin of a pagan building, on which workmen can be seen, apparently repairing it. on the right are men on horseback fighting, and a sketch of a rocky landscape. The ruins are a possible reference to the Basilica of Maxentius, which, according to Medieval legend, the Romans claimed would stand until a virgin gave birth. It is supposed to have collapsed on the night of Christ's birth (in fact it was not even built until a later date). The ruins dominate a preparatory perspective drawing by Leonardo, which also includes the fighting horsemen. The palm tree in the centre has associations with the Virgin Mary, partly due to the phrase 'You are stately as a palm tree' from the Song of Solomon, which is believed to prefigure her. Another aspect of the palm tree can be the usage of the palm tree as a symbol of victory for ancient Rome, whereas in Christianity it is a representation of martyrdom--triumph over death-- so in conclusion we can say that the palm in general represents triumph. The other tree in the painting is from the carob family, the seeds from the tree are used as a unit of measurement. They measure valuable stones and jewels. This tree and its seeds are associated with crowns suggesting Christ as the king of kings or the Virgin as the future Queen of heaven, also that this is nature's gift to the new born Christ. As with Michelangelo's Doni Tondo the background is probably supposed to represent the Pagan world supplanted by the Christian world, as inaugurated by the events in the foreground. Leonardo develops his pioneering use of chiaroscuro in the image, creating a seemingly chaotic mass of people plunged into darkness and confusion from which the Magi peer towards the brightly lit figures of Mary and Jesus, while the pagan world in the background carries on building and warring unaware of the new revelation. Due to Leonardo's inability to complete the painting the commission was handed over to Domenico Ghirlandaio. The final altarpiece was painted by Filippino Lippi and is now also at the Uffizi. In 2002 Dr Maurizio Seracini, an art diagnostician alumnus of the University of California, San Diego and a native Florentine, was commissioned by the Uffizi to undertake a study of the paint-surface to determine whether the painting could be restored without damaging it. Seracini, who heads Editech,a Florence-based company he founded in 1977 focused on the “diagnostics of cultural heritage", used high-resolution digital scans as well as thermographic, ultra sound, ultra-violet and infra-red diagnostic techniques to conclude that the painting could not be restored without damaging it, and further, that only the underdrawing had been done by Leonardo da Vinci, the paint surface having been added by another artist. He stated that "none of the paint we see on the Adoration today was put there by Leonardo". As a reult of his diagnostic survey on the Adoration of the Magi, Seracini completed more than 2400 detailed infrared photographic records of the painting's elaborate underdrawing, and scientific analyses.[1] The new images revealed by the diagnostic techniques used by Dr Seracini were initially made public in 2002 in an interview with New York Times reporter Melinda Henneberger. [2]In 2005, nearing the end of his investigation, Seracini gave another interview, this time to Guardian reporter John Hooper.[3] Dr Maurizio finally published his results in 2006 - M. Seracini, "Diagnostic Investigations on the Adoration of the Magi by Leonardo da Vinci (2006) in The Mind of Leonardo – The Universal Genius at Work, exhibit catalogue edited by P. Gauluzzi, Giunti Florence, 2006, pp. 94-101.[4] The painting is the central item in the Andrei Tarkovsky's final film The Sacrifice.

Study for The Adoration of the Magi, 1478–1481 References

Bibliography: Costantino, Maria (1994). Leonardo. New York: Smithmark.External links

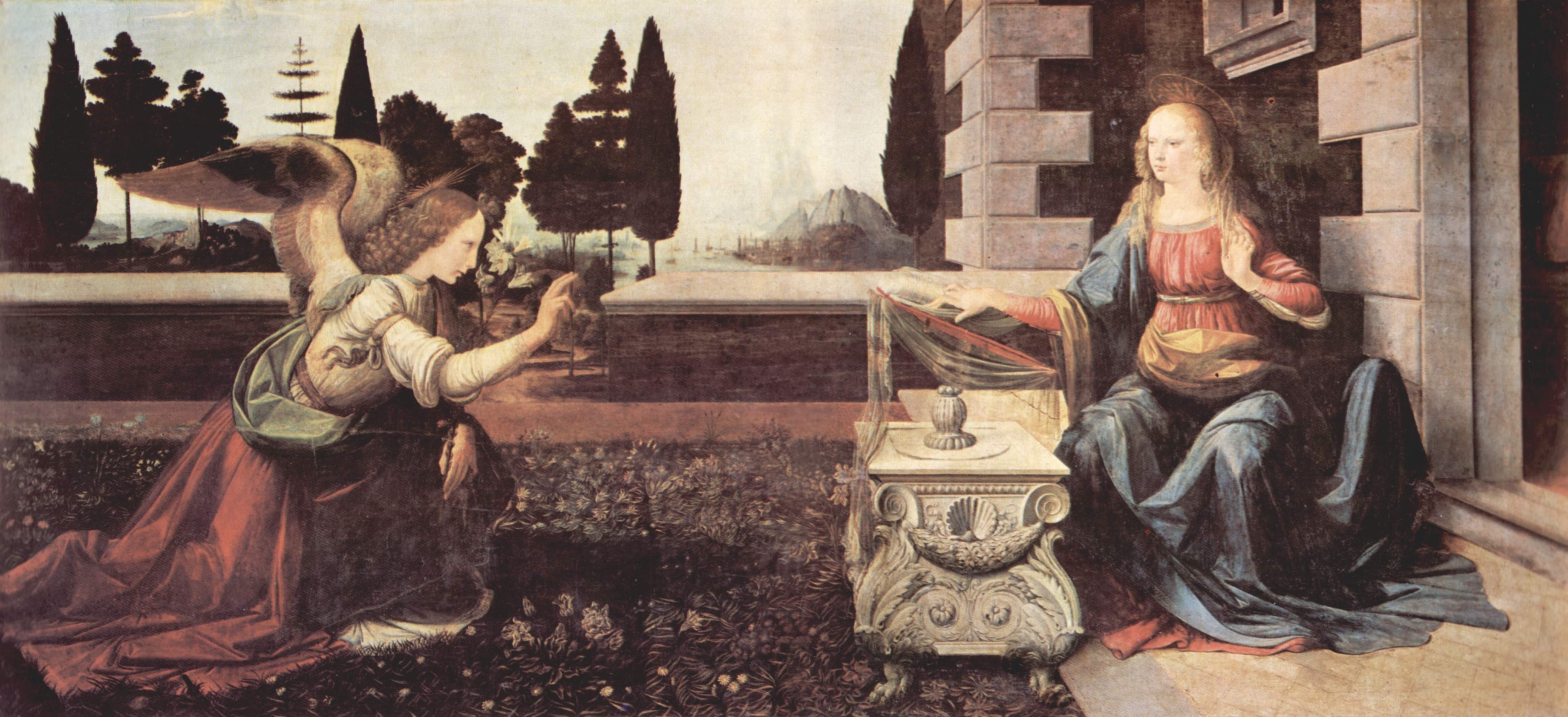

Perspectival study for The Adoration of the Magi, c. 1481 Adoration of the Magi (Mantegna)The Adoration of the Magi is a painting by the Italian Renaissance painter Andrea Mantegna, from 1462. Together with the The Ascension and The Circumcision, it forms a triptych created in 1827 at the Uffizi, where the picture can still be seen. The three works were acquired by the Medici in 1588 by the Gonzaga, whose member Ludovico had commissioned them to Mantegna in the 1460s for the Chapel of the Castle of St. George in Mantua (together with the Death of the Virgin, now in the Museo del Prado). The panel with the Adoration of the Magi was probably located in the chapel's apse. The Magi are depicted while descending to the Child's grotto from a path carved out in the rock. The Virgin is portrayed with a crown of angels, according to a Byzantine model. Reference: Page at artonline.it Annunciation (Leonardo)The Annunciation (1472–1475) is a painting by Leonardo da Vinci in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. It depicts the annunciation by the Archangel Gabriel to the Virgin Mary that she will conceive Jesus Christ and is set in the enclosed courtyard garden of a Florentine villa.[1] The angel holds a Madonna lily, a symbol of Mary's virginity and of the city of Florence. It is supposed that Leonardo originally copied the wings from those of a bird in flight, but they have since been lengthened by a later artist. When Annunciation came to the Uffizi in 1867 from the monastery of San Bartolomeo of Monteoliveto, near Florence, it was ascribed to Domenico Ghirlandaio, who was, like Leonardo, an apprentice in the workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio. In 1869, some critics recognized it as a youthful work by Leonardo. Verrocchio used lead-based paint and heavy brush strokes. He left a note for Leonardo to finish the background and the angel. Leonardo used light brush strokes and no lead. When the Annunciationwas x-rayed, Verrocchio's work was evident while Leonardo's angel was invisible. The marble table in front of the Virgin probably quotes the tomb of Piero and Giovanni de' Medici in the Basilica of San Lorenzo, Florence that Verrocchio sculpted in this same period.  Bacchus (Caravaggio)(c.1595) is a painting by Italian Baroque master Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571-1610). It is held in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. The painting shows a youthful Bacchus reclining in classical fashion with grapes and vine leaves in his hair, fingering the drawstring of his loosely-draped robe. on a stone table in front of him is a bowl of fruit and a large carafe of red wine; with his left hand he holds out to the viewer a shallow goblet of the same wine, apparently inviting the viewer to join him. Bacchus was painted shortly after Caravaggio joined the household of his first important patron, Cardinal Del Monte, and reflects the humanist interests of the Cardinal's educated circle. Whether intentional or not, there is humour in this painting. The pink-faced Bacchus is an accurate portrayal of a half-drunk teenager dressed in a sheet and leaning on a mattress in the Cardinal's Rome palazzo, but far less convincing as a Graeco-Roman god. The ripples on the surface of his wine look ominous: he will not be able to hold the pose much longer, and the artist had better hurry and finish the left hand.  The Baptism of Christ (Verrocchio)is a painting finished around 1475 by the Italian Renaissance painter Andrea del Verrocchio and his workshop. It is housed in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. Commissioned by the monastery church of San Salvi in Florence, where it remained until 1530, the picture was executed in the workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio, whose style is well defined by the figures of Christ and Baptist. The special fame of the work is due to the pupil who helped him paint it. The blond angel on the left and parts of the landscape background belong to the hand of the very young Leonardo da Vinci, who was in Verrocchio's workshop around 1470. Some critics ascribe the second angel to another young Florentine artist, Sandro Botticelli. David Alan Brown has a detailed and most interesting treatment of the Verrochio workshop and a long discussion of this picture, representing the most recent scholarship. [David Alan Brown, Leonardo da Vinci: Origins of a Genius. Yale University Press. New Haven, 1998.]

The Battle of San Romano (Paolo Uccello)is a set of three paintings by the painter Paolo Uccello depicting events that took place at the battle of San Romano in 1432. The three paintings are:

From Left to right:

The Uffizi panel was probably designed to be the central painting of the triptych and is the only one signed by the artist. The sequence most widely agreed among art historians is: London, Uffizi, Louvre, although others have been proposed. They may represent different times of day: dawn (London), mid-day (Paris) and dusk (Uffizi) - the battle lasted eight hours. In the London painting, Niccolò da Tolentino, with his large gold and red patterned hat, is seen leading the Florentine cavalry. In the foreground, broken lances and a dead soldier are carefully aligned, so as to create an impression of perspective. The three paintings were designed to be hung high on three different walls of a room, and the perspective designed with that height in mind, which accounts for many apparent anomalies in the perspective when seen in photos or at normal gallery height. The armour of the soldiers, and many other areas, were painted using silver leaf, which has now oxidized to a dull grey or black; the original impression of the burnished silver would have been dazzling. All of the paintings, especially the Louvre one, have suffered from time and early restoration, and many areas have lost their modelling.[1] Doni Tondo (Michelangelo Buonarroti)The Doni Tondo or Doni Madonna is the one of only three surviving panel paintings by the Italian Renaissance master Michelangelo Buonarroti (c. 1503), and the only one to be finished. It is in the Uffizi of Florence in its original frame, designed by Michelangelo himself. The painting was likely commissioned by Agnolo Doni, a wealthy weaver, to commemorate his marriage to Maddalena Strozzi of theStrozzis, a powerful Tuscan family. The painting is in the form of a tondo, or round frame, which is frequently associated with marriage in the Renaissance. The work was created during the period after the Roman Pietà and before the Sistine Chapel ceiling frescoes. It was influenced by Leonardo da Vinci's The Virgin and Child with St. Anne, as well as a work by Luca Signorelli and cameos in the Palazzo Medici. The Doni Tondo features the Holy family (the Christ child, Virgin Mary, Saint Joseph, and Saint John the Baptist. The background contains several ambiguous nude male figures. The inclusion of these nude figures has a variety of interpretations. SourcesThe composition is based on the cartoon for Leonardo da Vinci’s The Virgin and Child with St. Anne.[1] Michelangelo saw the drawing in 1501 while in Florence working on the David.[1] Like the earlier cartoon, Michelangelo’s figures seem to be compacted into very little pictorial space and a similar bilaterally symmetrical triangular composition is employed.[1] The work is also associated with Luca Signorelli’s Medici Madonna in the Uffizi.[2] Signorelli’s work depicts similar unexplained nude male figures in the background.[3] Like the Doni Tondo, Signorelli’s work is a tondo, which displays the Virgin sitting directly on the earth.[4] Michelangelo probably knew of the work and its ideas, and he wanted to incorporate them into his own work by improving them.[4] Three aspects of the painting can be attributed to an antique sardonyx cameo and a fifteenth century relief from the circle of Donatello, both of which were available to Michelangelo in the Palazzo Medici: the circular from, masculinity of Mary, and the positioning of the Christ Child.[2] The Virgin’s right arm mirrors the arm of the satyr.[5] The Christ Child, who is located on the shoulders of both the satyr and Mary, holds himself up by placing his hands on their respective heads.[5] Moreover, the two-dimensional effect created by having the central figures so close to the picture plane, mirrors the similar technique seen in antique reliefs, including the cameos.[5] CompositionThere is a horizontal band separating the foreground and background, whose function is to separate the Holy Family from the background figures and St. John the Baptist.[1][4][5] The far background contains a landscape.[6] The surface treatment of the massive figures resemble a sculpture more than a painting.[7] The Holy Family is set apart because of their special sanctification and are much larger in size than the nudes in the background.[4]There appears to be water in between the land where the Holy Family is situated and the nudes in the background.[4] It most likely refers to baptism.[8] The Holy Family all gaze at Christ, but none of the nudes look directly at him.[9] Holy FamilyThe Virgin is the most prominent figure in the composition, taking up much of the center of the image.[6] The Virgin is shown in an authoritative manner.[3] Mary sits directly on the ground without the cushion between herself and the ground, to better communicate the theme of her relationship to the earth.[10] The grass directly below the figure is green, which sharply contrasts to the grassless ground surrounding her, a theme that helps communicate the idea of salvation.[10] She was sanctified to have a direct role in salvation.[10] This theme is known as the Virgin of Humility, where the Virgin sits directly on the ground.[10] The green grass represents salvation and the dirt represents the damned.[10] Joseph represents a triple role as the father of Christ, head of the Holy Family, and the husband of Mary.[4] As the father, he named Christ, held him as a baby, and taught him literacy.[4] As the head of the family, he took care of them and covered up Christ’s miraculous birth until the time of his ministry.[4] As a husband, he cared for Mary.[4] In the image, he has a higher position in the image compared to Mary, as the head of the family.[4] He is also holding the Christ child like a father-figure.[4] Mary is located between his legs, as if protecting her.[4] Joseph’s triple role began to increase in importance and emphasis during the fifteenth century, including the belief by some that he also received sanctification before birth.[4] John the Baptist is a traditional inclusion of Florentines in works depicting the Madonna and Child.[1] Moreover, the first four sons of Angelo Doni and Maddalena Strozzi-Doni, were named Giovanni Battista (after the saint) before they died shortly after being born.[11] He his in the same space as the nudes, but is set apart from them by his posture and size.[4] John, like the other members of the Holy Family, received sanctification before birth.[12] He, however, is placed in the area between Divinity and sinners.[12] The elements around the figure, such as the plants, sinners, and water represent salvation through baptism.[8] NudesThe nude figures of the background are leaning or sitting on a half-moon, which is a common element in the Strozzi arms.[1] The two nude youths on the right of the work have been interpreted as homosexual lovers.[3] Other explanations for the inclusion of the figures include that they are shepherds, people waiting to be baptized, athletes of the Church, wingless angels, the five major prophets of the Old Testament, or the various ages of man.[12] They might be interpreted as the sinners who have removed their clothes for cleansing and purification through baptism.[8] The water, which separates the sinners from the Holy Family can therefore be seen as the “waters of separation” mentioned in theBible.[8] If this interpretation holds true, then the figures on the right represent the origins of the bisexuality of humankind and are waiting to be cleansed of their sins.[8] Their place near John the Baptist with a cross refers to the hope that all sinners have of being forgiven of their sins and can be purified through baptism.[13] A feminine looking youth figure is located on the right, which may stand for the human soul.[8] Michelangelo also depicts the human soul as a feminine form in the creation of man scene on the Sistine ceiling.[8] In Florence, there had been a debate from the middle fifteenth century until around the time this image was created, which discussed the immortality of the human soul and its place in the universe.[9] Michelangelo visually depicts the argument of Marsilio Ficino, who believed that mankind was central in the universe and could reach the sphere of God with the correct behavior.[9] The five figures may also represent the five parts of the soul: the higher soul (soul and intellect) on the left and the lower soul (imagination, sensation, and nourishing faculty) on the right.[9] Another explanation is that the group of two figures represent the human and divine natures of Christ, while the other three represent the Trinity.[9] In contrast, the three figures on the right could also refer to earthly love. The two men embracing could stand for reciprocal love, while the third could stand as the unrequited lover.[13] Earthly love leads to the resurrection of the soul, and without it, the soul is dead.[13] If this interpretation is correct, the Holy Family would most likely stand for Divine Love.[13] Plant symbologyThe plant in front of John the Baptist has aspects of both hyssop and cornflower.[12] Cornflower is an attribute of Christ and symbolizes Heaven.[12] Hyssop symbolizes both the humility of Christ and baptism.[12] Because it grows from a wall, it is likely a hyssop.[12] There is a citron tree in the background, which represents the Cedar of Lebanon.[12] Michelangelo uses the hyssop and tree as a visual representation of a quote by Rabanus Maurus, "From the Cedar of Lebanon to the hyssop which grows on a stony wall we have an explanation of the Divinity which Christ has in his Father and of the humanity that he derives from the Virgin Mary."[12] The clover in the foreground represents the Trinity and salvation.[12] The anemone plant represents the Trinity and the Passion of Christ.[14] ExplanationsThere are a multitude of interpretations for the various parts of the work. Most interpretations differ in defining the relationship between the Holy Family and the figures in the background.[6] One interpretation is that the image reflects Michelangelo’s views on the roles of the members of the Holy Family in human salvation and the soul’s immortality.[6] The Virgin’s placement and emphasis is due to her role in human salvation.[6] She is both the mother of Christ and the best intercessor for appealing to Christ. The image follows a Maculist point of view, which is a philosophy of the Dominican order, rejecting the idea of the Immaculate Conception.[6] Instead, the image depicts the moment of Mary’s sanctification, which is the moment of the incarnation of Christ.[15] Michelangelo, who had been strongly influenced by the Dominican Fra Girolamo Savonarola in Florence, is defending the Maculist point of view within the image.[6] The Christ Child blesses Mary as during a sanctification.[10] Michelangelo depicts Christ as if he is growing out of Mary’s shoulder to take human form.[10] One leg is hanging limply and the other is not visible at all, and therefore must still be apart of Mary.[10] Moreover, his muscles and balance convey an upward movement, as if he is growing out of her.[10] He is above Mary because he is superior to her.[10] The Maculist view is that the Virgin did not receive her sanctification at birth, but at the moment of the incarnation of Christ.[4] Another explanation is that the nudes in the background represent “the epoch before the Law”, the Holy Family represents “the era of Grace”, and John the Baptist represents the time between.[3] The Doni Tondo is the only existing panel picture Michelangelo painted without the aid of assistants.[1][16] The juxtaposition of bright colors foreshadows the same use of color in Michelangelo’s later Sistine ceiling frescoes.[1] The folds of the drapery are sharply modeled.[1] Skin of the figures is so smooth, it looks as if the medium is marble.[1] The nude figures in the background have softer modeling and look to be precursors to the ignudi, the male nude figures, in the Sistine Ceiling frescoes.[1] Michelangelo’s technique includes shading from the most intense colors first to the lighter shades on top, using the darker colors as shadows, which is a technique called cangiante.[17] The masculinity of Mary could also be explained by Michelangelo’s use of male models for female figures.[5] The central figures are silhouetted against the background.[3] The most vibrant color is located within the Virgin’s garments, which signifies her importance within the image.[3]

|  Adoration of the Magi; Filippino Lippi, 1496; Oil on panel; 258 cm × 243 cm (102 in × 96 in) Adoration of the Magi; Filippino Lippi, 1496; Oil on panel; 258 cm × 243 cm (102 in × 96 in)  Adoration of the Magi; Leonardo da Vinci, 1481; oil on wood; 246 cm × 243 cm (97 in × 96 in) ControversyOn March 12, 2007, the painting was at the center of a furor between Italian citizens and the Minister of Culture, who decided to place the picture on loan to exhibit in Japan.[2][3] NotesThe fruit and the carafe have attracted more scholarly attention than Bacchus himself. The fruit, because of the inedible condition of most of the items, is believed by the more serious-minded critics to signify the transience of worldly things. The carafe, because after the painting was cleaned, a tiny portrait of the artist working at his easel was discovered in the reflection on the glass. Bacchus' offering of the wine with his left hand, despite the obvious effort this is causing the model, has led to speculation that Caravaggio used a mirror to assist himself while working from life, doing away with the need for drawing. In other words, what appears to us as the boy's left hand was actually his right. This would accord with the comment by Caravaggio's early biographer, the artist Giovanni Baglione, that Caravaggio did some early paintings using a mirror. English artist David Hockney made Caravaggio's working methods a central feature of his thesis (known as the Hockney-Falco thesis) that Renaissance and later artists used some form of camera lucida. External linksThe painting portrays St. John the Baptist baptizing Jesus by pouring water over his head. The extended arms of God, the golden rays, the dove with outstretched wings, and the cruciform nimbus show that Jesus is the Son of God and part of the Trinity. Two angels on the riverbank are holding Jesus' garment. The composition as a whole is attributed to Verrocchio, as master and head of the workshop, and large parts of the painting are considered his work. Leonardo's angel has excited so much special comment (and mythology), that the importance and value of the picture as a whole has been somewhat overlooked. It is one of Verrochio's masterpieces. Provenance The three panels were commissioned by the Bartolini Salimbeni family. After the death in 1479 of the head of the family they were so coveted by Lorenzo de' Medici that he had them forcibly removed to the Medici palace at Florence, probably in 1484. They are recorded at the Palazzo Medici in an inventory of 1492.[1] The three paintings remained in the Medici (by now Grand-Dukes of Tuscany) collection until the late 18th century. The London painting was bought by dealers from another Italian collection in 1844, and bought by the National Gallery in 1857. The Louvre painting was one of many looted by Napoleon that were never returned; he is reputed to have hung it in his bathroom. Reference: 1.^ a b c National Gallery Catalogues: The Fifteenth Century Italian Paintings, Volume 1, by Dillian Gordon, 2003, pp. 378-397 ISBN 1857092937 |

Collections of the Uffizi

'Beautiful World of Arts' 카테고리의 다른 글

| Symphony of Science: 'We Are All Connected' (0) | 2009.11.26 |

|---|---|

| Adoration of the Magi by Leonardo Da Vinci (0) | 2009.11.22 |

| Perspective Study by Leonardo Da Vinci (0) | 2009.11.22 |

| Michelangelo books and, (0) | 2009.11.22 |

| 천마도 자료 (Unicorn/ Pegasus) (0) | 2009.11.11 |