William Blake I should state that from this point on the number has no correlation to where I imagine the artist falling in my personal pantheon. The first 4 are permanent fixtures in my mind. From here onward the order might (and probably would) change from day to day... depending upon my mood. I've already written an extended post upon Blake here in the "Poetry Redux" thread on the Poetry Forum: one of the most misunderstood and maligned of any major poet/artist. He is often portrayed as a half-mad genius/ visionary who spoke to spirits, a political naif, a curmudgeon and "outsider", a self-taught artist and poet who had little knowledge or experience of the art of his predecessors or of his own time. Most of these stereotypes have little reality to them. Blake attended virtually no formal school but was largely self-taught through his own voracious reading. He was exceptionally well-read and often of literature which was not part of the accepted canon of his time. Of course Shakespeare, Dante, Milton, Chaucer, Ben Jonson, Spencer, and especially the Bible were more than familiar to him... but other sources of inspiration include Thomas Paine and Mary Wollstonecraft, with whom he was friends and a political ally, Emanuel Swedenborg, Jean Jacques Rousseau, Plato, Plotinus, the Hermetica and the Bhagavad Gita, mythologies of the world from Egypt to Iceland to India to ancient Britain and even the Kabbalah. copying engravings of masters such as Raphael, Michelangelo, and Albrecht Durer. In this he was was fully supported by his father. Unable to afford apprenticeship to a painting master, Blake was initially apprenticed to the fashionable William Ryland, engraver to King George. Blake however would request that his father find a more suitable match for his talents, declaring that Ryland had "the hanging look about him". (In fact Ryland would end on the scaffold some years later, convicted for forging currency.) Blake spent his apprentice years under James Basire. Basire's manner of working was rather out-dated stressing the linear contours and avoiding the more painterly affects that would allow for replication of paintings or the creation of more atmospheric elements. His manner, however, was perfectly suited to Blake's own personal preferences for the linear sculptural form. Basire's chief source of income was the result of commissioned engravings to be made of architectural and sculptural details of English churches and cathedrals. Through his apprenticeship to Basire, Blake was exposed to the stylistic abstractions of Romanesque and Gothic art which would have been largely dismissed by most artists of the time. Blake's own art was often criticized as being crude and amateurish... full of incompetent distortions of anatomy... but in reality its stylizations are clearly consciously thought out and rooted in the artist's love of the linear art of medieval sculpture (among other sources). Rembrandt, etc... and well as their British heirs, Gainsborough, Turner, Raeburn, Romney, etc... At a time when landscape and portraiture in oil paints reined supreme, Blake had the audacity to produce his own versions of the illuminated manuscript ala medieval artists...

As an artist obsessed with books, William Blake would most certainly need to included among any list of my idols.

http://www.online-literature.com/for...ad.php?t=29869

I'll not go into such depth... but focus more exclusively upon his contributions as a visual artist. Blake has also been

Blake's talents as a visual artist, however, were recognized far earlier. He developed an early love of drawing by

Blake entered the Royal Academy but immediately rebelled against the painterly masters then favored: Titian, Rubens,

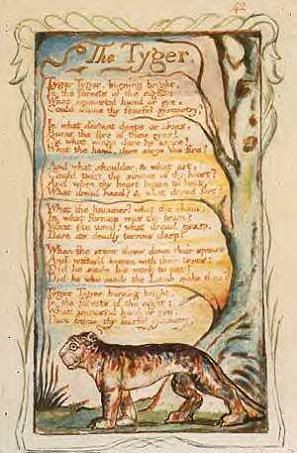

Among Blake's earlier works are his Songs of Innocence and Experience in which the short, lyrical poems are illustrated

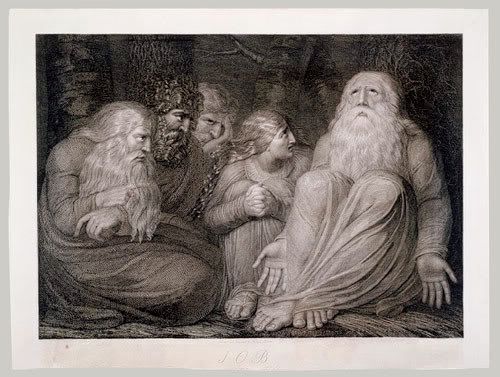

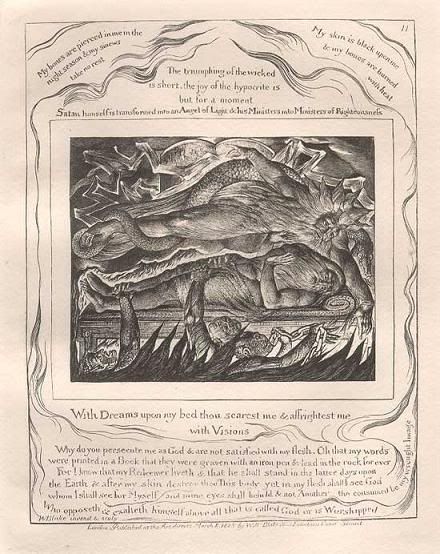

Among one of Blake's most fascinating works is hisJob.

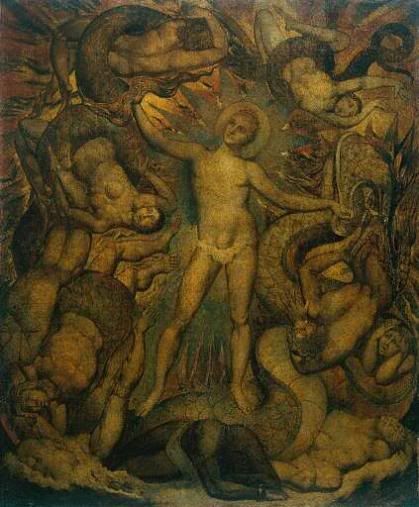

Blake presents a Job condemned to the fires of Hell. Devils reach out from the hell fires below in an attempt to drag him

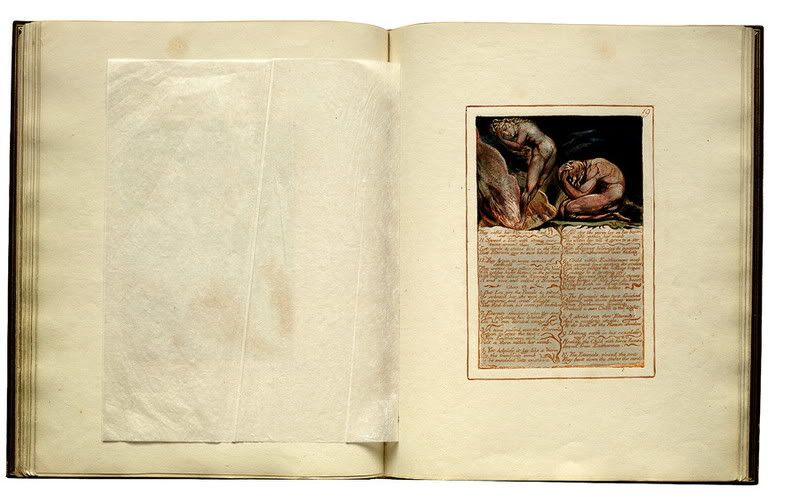

In the Book of Urizen Blake presents some of his most powerful visual images: muscular demi-urge figures in the

| #119 | |

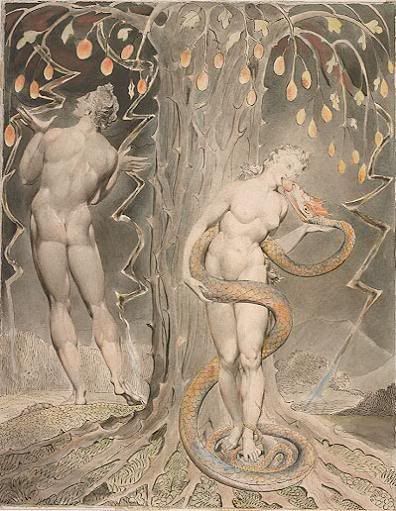

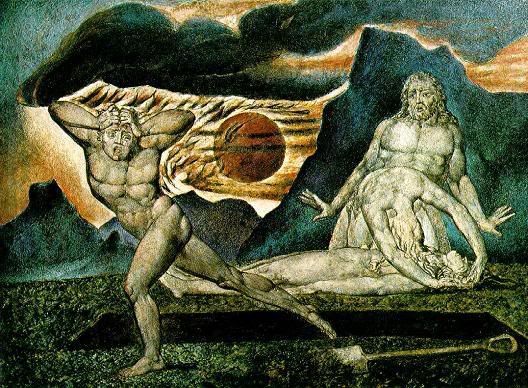

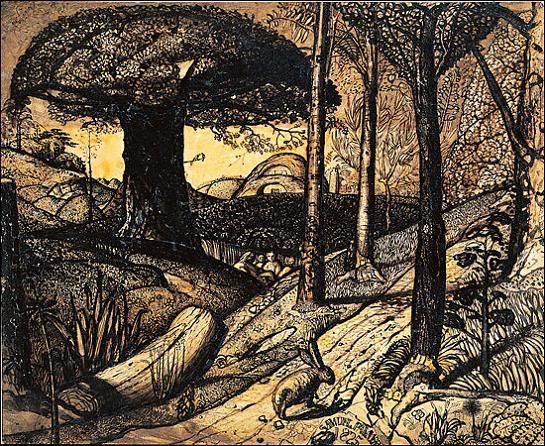

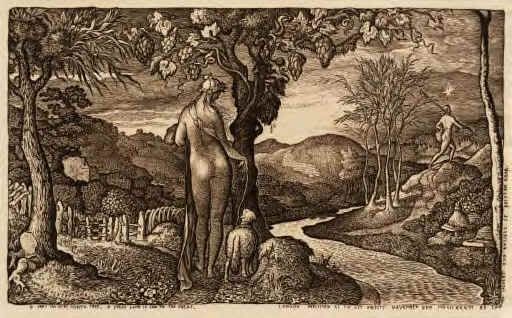

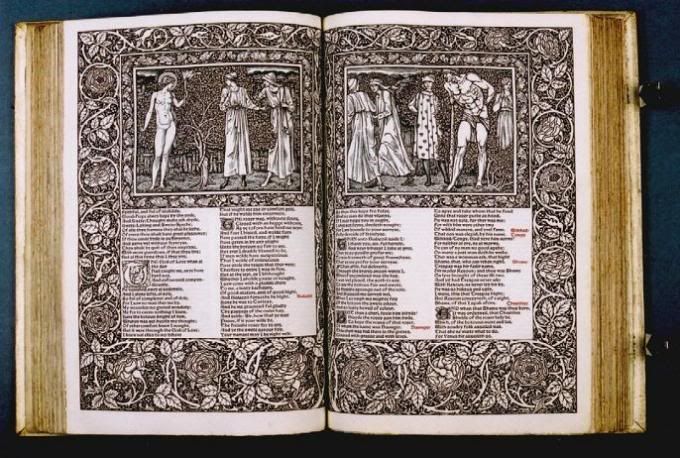

Beyond his illuminated books, Blake produced endless volumes of larger watercolor paintings as designs for never realized books... books that perhaps would have demanded technical facilities beyond those possible at the time. These watercolors include some of Blake's most memorable images: Scenes from Dante:    Marvelous imaginings of Milton's Paradise Lost:  Biblical narratives:   This final image... a Last Judgment almost blends the iconography of the Last Judgment with Christ's Harrowing of Hell or a Fall of the Rebel Angels in a manner that is very much suggestive of some Asian paintings! Blake's impact was slow to evolve... in art as well as in literature... but there are numerous obvious heirs. A group of young followers of Blake, including Samuel Palmer and Edward Calvert, who titled themselves "The Ancients" would produce a body of graphic works clearly inspired by their idol:  Samuel Palmer-Early Morning  Edward Calvert-The Bride Even more important was the great British artist/writer/political figure, William Morris, whose masterwork, The Kelmscott Chaucer, designed by himself and Edward Burnes Jones, was deeply indebted to Blake:  Perhaps most fascinating is the early 20th century figure of Adolf Wolfli, an artist confined to an asylum for most of his adult life, Wolfli produced a body of illustrated books, the central tome being a volume some 25,000 pages long, which tells the mythical story of Adolf Wolfli, later King Wolfli, later Emperor Wolfli, and finally Saint Wolfli. The tale is told in text, endless pictures, and even a musical score which utilizes a system of notation invented by the artist. There are endless similarities of style and vision in both artist's self-created universes... except that the latter artist is usually accepted as having been insane... a genius... but insane... which when looking at both his and Blake's achievements leads us to some difficult questions about what constitutes genius... and what constitutes insanity.  ㅡ http://www.online-literature.com/forums/showthread.php?p=590212 |

'Beautiful World of Arts' 카테고리의 다른 글

| "Exploring The Invisible" by Lynn Gamwell (0) | 2009.01.24 |

|---|---|

| 윌리암 블레이크의 '신비'주의 (Mysticism) (0) | 2009.01.10 |

| 드로잉 tips: "Portrait Drawing" (0) | 2008.12.27 |

| Mother Mary and Beloved Jesus (0) | 2008.12.20 |

| 쇼팽: Nocturne Op.9 No.2 (0) | 2008.12.20 |